Ulster Workers' Council Strike at 50: Loyalist Perspectives - Glen Barr

This is the second in a series of transcripts from a conference I co-organised in 2014 at Queen’s University Belfast. The first, featuring the late Henry Sinnerton can be found here.

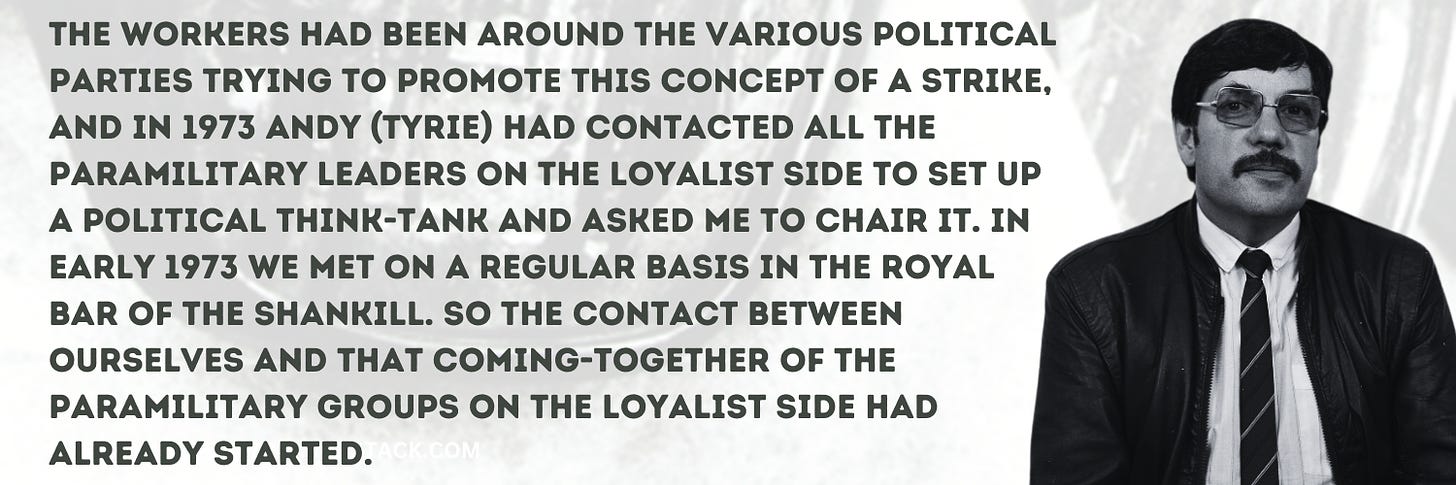

The late Glen Barr was a trade unionist, leading member of the UDA and a strike leader in May 1974.

Photo: Brian O’Neill

“Could I just say that Queen’s brought me out of retirement two years ago to speak on behalf of the UDA, and Connal succeeded in doing it today again when I was going back into semi-retirement. I’ve been trying to put some things together and this is probably the worse piece of paper I’ve ever had to put together because of the fact that it’s forty years ago. The thing about it was that the very famous (Harold) Wilson speech in which we all thought we were going to be interned led to the point where all my notes were destroyed in case the authorities got their hands on them – and that unfortunately has been a piece of history that’s been lost to us, and the only thing that was left was my last day’s notes which are not very exciting. But all the other stuff which involved the setting-up of subcommittees to take over the Strike were all destroyed, and also their second committees. So we can appreciate in those days we didn’t keep notes – the idea was you destroyed everything you wrote – and unfortunately now at 72 years of age my memory is not what it used to be. So with the aid of a friend of mine here in Queen’s – he gave me a few dates, I’m sure you know all the dates anyway yourself – I think you’ll be more interested in some of the details.

How did I come to be involved in what happened? In 1972 we had a delegation of sixteen people that went to the House of Commons to lobby the MPs in relation to the upsurge in Republican violence, and I was one of the three-man delegation that was selected to put our case to Reginald Maudling, the then-Home Secretary. We spent about an hour-and-a-half with Maudling, who made commitments and promises to us in relation to the rumours that were circulating throughout Northern Ireland that the B-Specials would not be disbanded; that the RUC would not be disarmed. And I suppose a bit like the beginning of the Second World War, we headed off with this piece of white paper thinking this was it – ‘done deal’, and that the British Army would be strengthened to oppose the nationalist and the Republican campaign. Two weeks later, not only did we not get the protection for the B-Specials and the police force/RUC – the B-Specials were disbanded, the RUC was disarmed. Not only that but our legitimate and constitutional parliament was abolished by Westminster: without any consultation, without any thoughts about how this was going to leave the Protestant/Loyalist people at home. I vowed at that time that never again would I trust an English politician. I’m now 72 years of age, and since that time I have never done that.

I indeed went on to declare in the House after I was elected in ’73 that ‘I’m a first-class Ulsterman, I’m not a second-class Englishman, and I have no intentions of becoming a third-class Irishman’. Later I went on to stress when I was in Stormont that I had become an Ulster Nationalist, and I hold that view to this day – and it’s all because of Reginald Maudling and my distrust of English politicians. That led on to all the work that I did do then in relation to independence and the whole concept of the people of Northern Ireland putting Northern Ireland first and working out our political structures to ensure that everybody participated in the responsibilities – the decisions – of the state, protected by a Bill of Rights. I believe that if we had gone down that road we might have saved a lot of the deaths that occurred in this country.

It was because of my distrust of politicians that I changed my whole attitude to what we should be doing here in Northern Ireland. It came about as well from the fact that my grounding was in the trade union movement. I never wanted to be a politician. If I had got up one day and I was a politician or somebody told me I was, I’d have never have believed them. But it happened because when the going got tough out there on the sticks, Loyalist politicians all ran for cover. Our Churches were abysmal, had no record whatsoever of being involved with our communities, and our communities were left leaderless. There was nobody in our communities to give leadership to the Loyalist community. So people like myself and others throughout the country were thrown up to try and give some responsibility and leadership to our people. So with that in mind I felt that never again would I trust anybody with my security and never again would I trust anybody – particularly English politicians – with the future of my country. I later made a statement in the House when I said that I ‘had no intentions of fighting British soldiers to remain British. But I’ll fight everybody or anybody to stay out of a United Ireland’, and I still hold that view today.

From the outbreak of the Troubles in 1968 until 1974, the Unionists believed that they had suffered a series of political defeats. The failure of security forces to defeat the IRA, and then the plans of the British government for a whole new administration in Northern Ireland suggested that people like Gerry Fitt, John Hume and the SDLP were going to be in our government. These were the very people who had been involved in the destruction of our country and the destruction of our democratically-elected government. They were also there now making political gains on the back of the IRA and as far as we were concerned the process had to be stopped. So in 1973 the government issued the White Paper on Ireland’s constitutional proposals, which included plans for a Northern Ireland Assembly elected by PR and the stipulation that the Executive should have widespread support; that crucially, given how events had developed, a Council of Ireland must operate with the consent of both the majority and the minority. That’s a bit of a turnaround when you think of 1972 – the Whitelaw government disbanded our security forces and never had one word to talk to us about it.

It was around this time that Bill Craig, Vanguard leader, wrote to the party members stating: ‘If the Executive can’t be prevented from getting new proposals off the ground as a credible institution, it will survive long enough to bring the unification of Ireland meaningfully closer’. Craig believed that Unionist opposition in the Assembly would be ineffective as it could be ignored by the Secretary of State, and that the campaign would be won or lost in the country. Significantly, he added: ‘The form of organization is all-important. It must provide a coming together and must be free of the personality cult. People must be able to identify without feeling disloyal to the existing commitments without having to join an already identifiable organization. A Loyalist action council (or central body) to which constituency associations of political parties could affiliate seems a necessary starting point to be followed by action groups in every county, town, village and factory and suitable workplace’.

One form of opposition which was clearly on the Loyalist agenda was an industrial stoppage. The stoppages had worked well for Vanguard in March 1972 at the time of the suspension of Stormont, but it proved disastrous in February 1973 when a protest strike against the internment of UDA members had been characterized by widespread violence. The consequences of the February 1973 strike was the effective collapse of the Loyalist Association of Workers (LAW), and now attempts were being made to create a new Loyalist workers organization. An early indication of this came on the 2 November when the Belfast Telegraph reported on the formation of a group called East Antrim Loyalist Workers which had split from LAW and which significantly included Ballylumford power station.

At that time there was a whole international problem with power cuts and the Yom Kippur War between Syria and Israel, and crucially the Arab oil states began increasing prices. So there was mayhem all over the world at that time, but more particularly in the UK. I can remember to this day – and I see my old friend Maurice Hayes there – one distinguished Lord in Parliament at Stormont, who made an effort for us to save fuel, whereupon on his statement in the House he dropped his trousers to show us all that he was wearing his long johns, and he said that we should all adopt the same attitude. I think he was the only one who took up the idea himself! (laughter)

But there were serious problems all over the country and there was no doubt that the difficulty came in the 1973 elections in which Harold Wilson was defeated and we got Heath. He was then defeated in February after that, and Wilson then took over. The whole election in February 1974 was the question ‘Who governs Britain?’ However the result failed to produce a clear winner, and the Conservative leader Edward Heath’s post-election attempts to reach an Agreement with the Liberal Party failed, and on 5 March a minority Labour government led by Harold Wilson took power. By 20 November that year the government’s White Paper plans for Northern Ireland still appeared to be progressing when the Ulster Unionist Council narrowly voted not to reject power-sharing, and late-November also saw the meeting at Vanguard Headquarters of a group that would eventually become the Ulster Workers’ Council. Loyalist trade unionist Harry Murray had been invited to the meeting to represent Harland & Wolff, and agreed to participate in the new organization provided politicians and paramilitaries were not represented.

Although Murray’s provision was agreed to, the reality was that paramilitaries and politicians remained close to the working of the UWC, if not an integral part of it. One of Harry’s closest allies in the following months for example was Bobby Pagels, who was a prominent UDA member. What emerged therefore was a situation where there was a rough compromise between workers, paramilitaries and political groups as to who was to lead, or play the primary role, in the campaign against Sunningdale. In the longer term this also led to competing claims from the various elements as to who was the real force behind the Strike.

By this time Andy Tyrie had been elected as the temporary chairman, for want of a better word, to avoid a split between (Charles) Harding Smith in the West and Tommy Herron in the East. Andy was now well-established as the Chief and was slowly building a team around him to deal with all aspects of life in the Loyalist areas. I was not present at the inter-council meeting which took the decision to appoint Andy, but as the political spokesman for the organization I was called in immediately afterwards and informed of the decision.

As was well-known at that time there were attempts on Andy’s life and as political spokesman I came out publicly in support of Andy Tyrie, and not only over the years did him and I work very closely together but we also became great personal friends. I suppose he’s not here to defend himself but Andy’s an unassuming character – to those of us that know him very well – with a magnetic personality, and I think the press in those days would tell you that. We got our message across but in most cases we didn’t take life too seriously at that time, and that’s not in order to play down the actions of the organization or how we felt about things. But I think that he and I both never really fully appreciated the position that we had held and therefore we could always see the day when we’d return back to the shop floor – me to continue with my trade union future (I hoped), and Andy was going back to his gardening. Unfortunately we weren’t allowed to do that.

What he did do was restructure the entire organization. He immediately set up structures to look after various elements within the organization like welfare, community development, and of course he was very much involved with me in the political side. He had done it very effectively and the attempts that were made on his life did not in any shape, form or fashion put him off the track that he believed was best for the organization and the best for the people of Northern Ireland. In all the years that I have known him his total commitment has been to providing a better way of life for our people. The workers had been around the various political parties trying to promote this concept of a Strike, and in 1973 Andy had contacted all the paramilitary leaders on the Loyalist side to set up a political think-tank and asked me to chair it. In early-1973 we met on a regular basis in the Royal Bar of the Shankill. So the contact between ourselves and that coming-together of the paramilitary groups on the Loyalist side had already started.

As the Sunningdale process progressed, Unionist opposition also coalesced with the formation of both the political umbrella the United Ulster Unionist Council and – the paramilitary equivalent – the Ulster Army Council. The Sunningdale communique outlined the provision for a Council of Ireland by 16 December when Austin Currie told RTE that it fulfilled Wolfe Tone’s desire to ‘break the connection with England’, and Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave told the Sunday press that there was no question of the Republic changing its territorial claims to Northern Ireland. The trend of growing Unionist opposition to Sunningdale became even clearer on 18 December when the North Tyrone Unionist Association – which was seen as a weather-vain of UUP opinion – voted by a ratio of 2 to 1 to support the anti-Sunningdale candidates, and even the pro-Faulkner Belfast Telegraph was now predicting that he would be defeated on the Sunningdale issue when the Ulster Council was to meet on 4 January 1974.

Despite this the anti-Sunningdale opposition was still not focussed on a single objective and on 22 December, for example, the UDA blocked roads in protest against the treatment of Loyalist prisoners. In mid-February 1974, meanwhile, two UDA men were shot dead by the Army and a third wounded during riots in East Belfast. On 4 January, as was widely predicted, Faulkner lost the Unionist Council vote on the proposed all-Ireland Council settlement and resigned as Party leader three days later. Alarm bells were now ringing in Belfast and London and on 17 January senior civil servant Sir Ken Bloomfield – whom I hope to see later on – wrote a political brief for Faulkner in which he warned that unless Sunningdale could be ratified with the consent of ‘the majority of the Protestant community’, it may not long survive on any ‘useful basis’.

Later that same day, however, SDLP Assembly member Hugh Logue told a Dublin audience that the Council of Ireland was the ‘vehicle that would trundle us into a united Ireland’. On the 28 February in the UK general election the UUUC won 11 of the 12 Northern Ireland seats with 51 per cent of the vote. The incoming Labour minority government – which had many other problems to deal with – were aware that the early implementation of the Council was highly unlikely, but were unable to convince either the SDLP or the Irish government of this hard reality, and Faulkner’s position continued to erode.

On 7 March 1974 the Newsletter mentioned the Ulster Workers’ Council for the first time when the UWC challenged the new Secretary of State Merlyn Rees to attend a victory rally for the UUUC general election candidates to be held at Stormont that Saturday afternoon. On 12 March anti-Sunningdale Unionists tabled a motion in the Assembly calling for the re-negotiation of the Sunningdale Agreement. On 23 March the UWC issued a statement threatening widespread civil disobedience unless fresh Assembly elections were called. Elsewhere in Northern Ireland tensions were further heightened by a renewed IRA bombing offensive and March saw the greatest number of security incidents of any month from 1974 (a total of 921 incidents), as well as the greatest number of explosions.

Two weeks later, against this background, Northern Ireland Office Ministers Merlyn Rees and Stanley Orme met the UWC representatives at Stormont in what was an angry meeting. Division within the UWC still continued however and the paramilitaries were angry at not being included in the UUUC conference held at Portrush between 24 and 26 April. Significantly, however, the conference saw Harry Murray and Billy Kelly being included as members of the UUUC Study Group, set up to devise a blueprint for trial-active sanctions as a means of implementing the will of the people. The question of the Strike in opposition to Sunningdale was now becoming more immediate. Billy Kelly of the power workers was pushing for an immediate strike, while Harry Murray wanted to wait until the Spring – partly to reduce the hardship the strike would cause.

By May the weather had improved while it also appeared that the success of the UUUC candidates in the General Election had also had no impact whatsoever on Sunningdale and that other actions might be required. Things were getting desperate at that time. I remember Bill Craig and I were sitting on the front benches at Stormont and the SDLP were sitting opposite. One after the other got up and they had been without a shadow of a doubt the most powerful team of politicians I have ever seen assembled at any time. One after the other they got up and spoke with not a note for fifteen minutes, on every subject that was effecting us, and they were absolutely superb. Brilliant they were, and Craig turned to me and said: ‘Glenny, I’ve just been thinking – Willie Whitelaw could defeat our whole campaign against the Sunningdale Agreement’. And I says, ‘What do you mean Bill?’ And he says, ‘He could defeat the whole thing in one foul swoop’. And I says ‘How’s he going to do that?’ He says ‘He could ask us to form a government’. I said what do you mean? He says, ‘Well look behind you – how the hell could you form a government from that?’ And I looked behind me, seriously, I looked at what was behind us, and what was in front of us – and there was no comparison whatsoever. We just could not compete with the SDLP. (And I’m sorry to say it appears that the same thing is happening today with people who have no place in politics at all being thrust into positions in politics because of their association with one organization or another.)

It was just after that that the UWC asked to talk to Andy. I wasn’t involved – I was at home – and they apparently had asked Andy to support the Strike and use the UDA to do that. When I was in Belfast most nights, if I didn’t make it down home I stayed with Andy and I was staying that night with him, and he told me that he had had a meeting with the UUUC leaders and they were looking for the UDA to back the strike. I said ‘Well when is the strike?’ He says, ‘They don’t know, they’ve no decision taken yet, and there’s a whole argument between them about when they will have the strike’. I said to him, ‘Well Andy, if the strike is going to be pinpointed against the Sunningdale Agreement, the time to have the strike would be the 14th of May, when the vote is being taken at Stormont’. And he said ‘Well, what’ll that do?’ I said, ‘Well we’re going to be defeated; we can’t win it. We don’t have enough votes in the House to win it’. So after I convinced him of that we called the UWC, and he set the date for the 14 May. Up until that time there was no date set. As history shows, the ball started to roll and on 14 May Harry Murray went up to Stormont and declared that the Strike would start.

I was making a note of this the other day because something very eerie happened – that day Hughie Smyth and I weren’t in the House for the vote. Hugh and I were at Long Kesh visiting the UDA and the UVF prisoners. After we had finished the tour of the Kesh, I went on home. I had been writing this down about Hughie and myself when I got the news that Hughie had just died, and I thought…that’s a very eerie thing that happened. Hugh and I had forged a great relationship, and a lot of what changed and made up my mind about politics was during the whole campaign against Sunningdale, the UUUC – Paisley and them – took a decision that we would not be allowed in the house. So we were effectively barred from going in to the Parliament, into the House. Hughie and I used to go to the public gallery and listen to the debates that were taking place, and it was plain to be seen on anybody’s face that there was no harmony in that Executive. You could see that there were political splits – and I don’t mean religious-political splits. I mean there were political splits that were occurring within the Executive. People like Paddy Devlin – who became a great personal friend of mine – and Gerry Fitt, who were coming from a trade union background, a working class background like myself and Hughie. So it wasn’t hard for us to develop an everlasting friendship with those fellas. And I always remember Gerry later, when we had a vote on the Voluntary Coalition (in 1975) – saying to me, ‘Glenny, the problem I have’ – I’ll not use the exact words Gerry used, Gerry could use a few choice words himself – but he described, ‘Them fucking Green Tories West of the Bann is my problem in the Party’. That’s how he described John Hume and the rest of the bunch in the SDLP.

The situation was then that the Strike kicked off. I wasn’t up; I was in the office in Derry and I got a phone call from Andy when he came on the phone and says, ‘You’re going to have to get up here right away’. I says ‘Why what’s wrong?’, and he says ‘It’s an absolute shambles up here, really is an unbelievable shambles. Glenny you need to get up right away’. So I dropped everything I was doing, battered up the road – a colleague with me – and I nearly didn’t make it because I think I’ve a fair reputation of being a bit of a low flyer. I reached Belfast and stayed with Andy, so that was me there now for the fortnight. We started talking it over and he said to me, ‘Look we’ll go in tomorrow morning, we’ll sort the things out. The leaders will be all there – there’ll be three from each of the paramilitaries and there’ll be six from the workers’. And immediately I thought, well that’s a hell of a size of a Committee to start with but let’s go and see what happens.

We went in in the morning and Billy Kelly was complaining that the workers were getting all the blame for this Strike, and they would need the paramilitaries to give them a hand. Of course wee Harry Murray, he wasn’t too keen on the paramilitaries getting too much involved. But it was a case of they had to get involved, and the UDA as the largest paramilitary group at the time was asked to take the lead in that.

I just felt that the whole thing was so unwieldy and there was no business being done really at all because every couple of minutes there would be a knock at the door and somebody wanted to speak to Andy Tyrie and Andy would leave for a while, and then next thing somebody would want to speak to Ken Gibson from the UVF and Ken had to go, and Billy Mitchell had to go. It was just out and in traffic the whole time. So eventually I got them all sitting down and I said, ‘If you want me to continue to manage this, first thing is I’m cutting this Committee down. There’ll be one from each of the paramilitaries and the workers can have three’. By that stage the only politician there was Bill Craig, who had declared – and I mean this seriously verbatim – ‘I don’t think this’ll work but I am in it, sink or swim, I’m here until the death’. For that statement Bill Craig seriously got all the support that he wanted from the paramilitaries after that.

Anyway I said to them: ‘Tomorrow morning we’ll meet at 9 o’clock – one from each and three from the workers’. And I put three men outside the door and said ‘I don’t care who comes, who knocks, who they’re looking for. Nobody gets out and nobody gets in’. So that was the attitude we adopted from day one. That meeting would have met for at least an hour and we got reports coming into us in the morning, and we then took decisions on how we would operate for the next 24 hours. At 10 o’clock we broke and had tea at Vanguard headquarters, and after tea at half past 10 the larger group assembled then and we brought three in from each of the paramilitaries and six in from the workers – and they were the runners who now had to distribute the information throughout the organizations. That was done very effectively.

Now, people say to me ‘That was a marvellous master plan you had.’ There was no plan at all. Seriously, we were on a wing and a prayer. The way I got out of it on numerous occasions was when people used to phone up and people used to talk – they had a complaint – I used to give them the phone number to the Northern Ireland Office and told them that was the number to ring with complaints. The next thing we heard was the Northern Ireland Office were complaining because their phones were all choc-a-bloc. But there was no master plan, and the workers – there was no doubt about it, Billy Kelly did a superb job as far as the power workers were concerned. The paramilitaries, they get blamed for heavy tactics and all the rest of it. But the one thing that Andy and I stressed throughout the whole Strike: there was to be no confrontation with the security forces. That would destroy us. So men who put up the barricades were told if the Army come along with their diggers, let them knock them down, go round the corner, build another one. They’ll not stay there 24 hours and as soon as they go away build it up again. So that was the attitude we adopted – no confrontation whatsoever, because that’s the very thing that’ll turn it against our people.

The only blight for me on the Northern side – the terrible happenings of Dublin took place of course, the three bombs that were set off at Dublin and Monaghan. For years I never thought it was any of our paramilitaries that done it. I thought it was the British, until I was then convinced that it was the UVF. But not being disrespectful; it was one of those situations that we were so engrossed in what we were doing ourselves, it was so important that the Strike Committee – and Andy and I in particular – got things right, that it just went over your head. The thing that brought it back to reality of course was the murder of the two brothers outside Ballymena, which again was a terrible thing. It was nothing to do with us but because the fellas were linked to the Strike, the Strike got the blame for it. What was important was that we did not have confrontation, any full-scale confrontation with the security forces would have destroyed the entire operation.

We reacted on a daily basis: we were getting phone calls from groups of workers over the country who wanted to come out on Strike. We analysed if it right to bring them out on strike or keep them going, and we took the decision that we felt best. Bobby Pagels was shifted down to the centre of the town – round E.T. Greens I think it was at the time, the feed suppliers to the farmers. He controlled all the foodstuff that were going to the farmers and was given carte blanch authority to decide what he thought was best at the time. There were other people who were given tasks throughout the country in various areas, and in particular because of the UDA structure there were representatives all over the country so it meant that easily the message could be passed down through the UDA, and hopefully with the support of the UVF and the other paramilitaries making up our barricades. We manned our protest points and people were frightened – there was no doubt people were frightened – but the whole concept was to get through to people that this was not another Vanguard two-day wonder. We were in this until the end and we were asking people to commit themselves to it.

Now there’s been an argument in history about should they have moved the (British) Army against us. I don’t know what the Army could have done, I really don’t. The only people who could have made any impact would have been to move the RUC in. It surprised me they didn’t take that decision, but they did in 1977 and we saw the fruits of that. But as far as the British Army were concerned, they were all told if the Army comes in let them knock your barricade down, go round the corner and build another one.

After the second or third day, the people in the streets had got so behind the Strike that there was no need for barricades anymore. They threatened to put the Army into the power stations, so we threatened to pull all the workers out. And I think that they had bad experiences before with them using the Army before in power stations, and by the time they’d gone back in again it cost them a fortune to try and repair the damage that had been done. Then of course as the Strike went on we manned our own stations for petrol and diesel, and when they put civil servants in to run the petrol stations we wouldn’t deliver to them. Then they decided that they were going to take over the distribution of bread, and I said to them, ‘You take over the distribution of bread, you’ll bake it’. They said ‘What do you mean?’ I said, ‘We’ll pull the bakers out’. They said ‘But you can’t do that’, I said ‘We just did it, we just told them to come out on strike’. The last one of course was the sewage workers. Then of course sewage was to be running down the streets and I think that scared the living daylights out of them.

I suppose that poor Paisley was always getting the butt of it. I remember distinctly there were two occasions after he did come in. First and foremost he didn’t come in anywhere near us, he was in Canada. Then he did arrive in – we had already started the first meeting at 10 o’clock, in the big bay window in Vanguard headquarters – and I saw him tramping in and the next I heard a bit of a kerfuffle outside the door but he never appeared. It turned out that they wouldn’t let him in. There were three burly lads outside and they said, ‘You’re not getting in’. He said ‘Do you know who I am?’, and I remember one lad, Jimmy, saying, ‘Ah we know who you are – you’re not as big a man out here as you are out in the street. There’s a man in there bigger than you and he’s telling me there’s nobody getting in here, nobody getting out. So you’re nether getting in nor getting out and you should stay there completely sober’. So that’s when he came in and the famous story of the chair occurred. I was out for my tea and the Carver chair was up at the top of the table, and when I came in he had plonked himself down on the chair. I said ‘Ian that’s my seat, you’ll have to move’. He started a whole story about ‘I have a bad back, I was travelling and a sore back’. I said ‘That’s alright, take the chair and move down the room, but that’s my seat – that’s where I’m sitting’. And he says ‘Can I not keep the chair?’ I said ‘Take the chair’. There were a couple of boys from Belfast minding the door and I says, ‘Will you give Ian a hand to shift that chair?’, so the three boys got round the chair, started lifting him chair and all, so he said, ‘Hold on, hold on!’ He very quickly jumped up then, so the back wasn’t as bad as he was telling us (laughter).

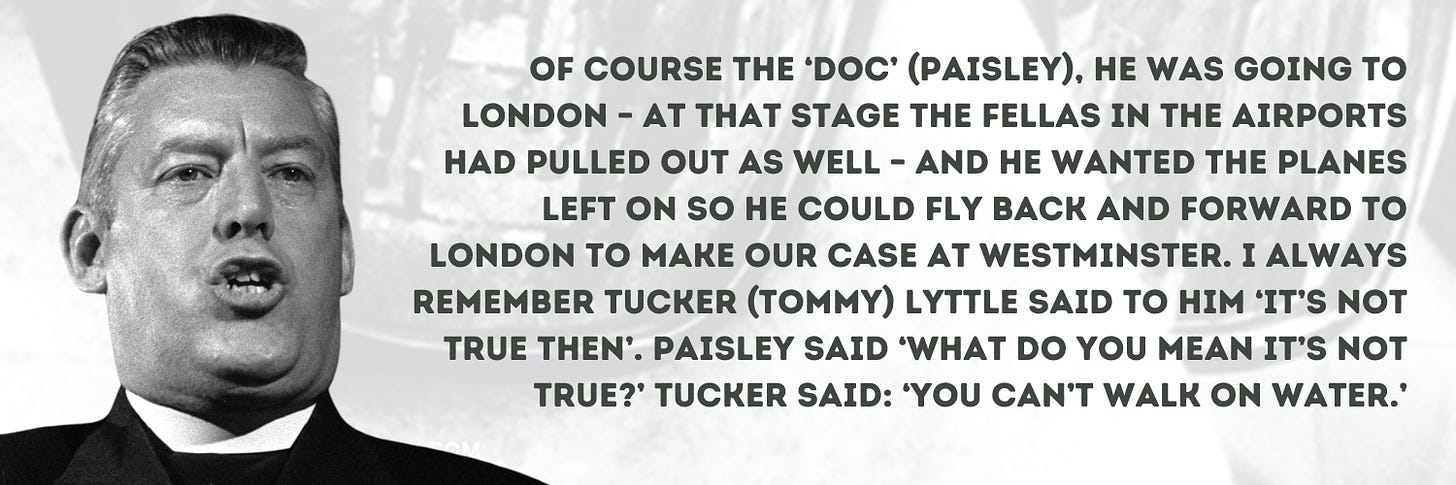

But on every occasion Craig was playing solidly with the group. The other two, Harry West and Paisley, were always trying to score something and get points throughout the country. I remember we had took a decision on feed for the farmers and we caught Harry West phoning out some farmers to say that he had got this stuff released to them. So he was told for the duration of the Strike he wasn’t permitted to use the telephone anymore. And, of course the ‘Doc’ (Paisley), he was going to London – at that stage the fellas in the airports had pulled out as well – and he wanted the planes left on so he could fly back and forward to London to make our case at Westminster. I always remember Tucker (Tommy) Lyttle said to him ‘It’s not true then’. Paisley said ‘What do you mean it’s not true?’ Tucker said: ‘You can’t walk on water.’ He didn’t take that too well! Of course then he asked for his buses to be run on a Wednesday night to the Martyrs Memorial Church. Andy Tyrie said ‘Ok, you can run your buses to the Martyrs Memorial Church, but you’ll let me lift the collection’, so he didn’t take that offer up (laughter). So that’s the way Big Ian was treated within the meetings.

The situation on the very last day of the Strike – I want to make this point very, very seriously because it certainly effects a lot of what people thought out there. Unfortunately it wasn’t taken on board; I had nothing to do with the 1977 Strike. I advised Andy not to have anything to do with it. Because they lost the very basic point: we did not defeat Brian Faulkner. We did not defeat the British government. The British government pulled their support for Brian Faulkner and he collapsed. Brian Faulkner was quite prepared to go on, and I’m sure Maurice (Hayes) will make that point. Brian Faulkner was quite prepared to go on if it had the support of the British government, and he was left with no alternative but to resign. On the very last day at Vanguard headquarters, when all the reports were coming in all over the country, Andy and I were heading back to his house that night at about 9 o’clock, and the people were lighting fires and they were out singing and dancing in East Belfast. We had to drive through them. It was the same when we got to the Shankill, when we got up to Glencairn (where Andy lived) the people were out in their hordes, bands were out, everybody was celebrating. As far as they were concerned the Strike was over.

Andy and I knew we had a very serious problem – we hadn’t won what we set out to achieve and that was fresh elections. When we drove back from Andy’s house the next morning to Vanguard headquarters, the people were going back to work, so I said to Andy ‘We have a serious problem now – we can’t continue the strike’, and he agreed. So when we got to Vanguard headquarters we called a meeting and said the Strike’s over, and I know there was one or two fellas who weren’t too pleased about it. But we knew that if the Strike was to continue Andy was going to have to put the UDA back on the streets and we were not prepared to do that. That defeated the whole concept of what the Strike was about. People didn’t like it, but they had to lump it.

As I say: people have argued over was it right, was it wrong? What was the Strike all about? But as I said at the start: the Loyalist people had taken such a terrible battering over those years from 1968 up to 1974. No consideration was given to them, about how they felt. There was no consultation with them when their government, their institutions, were taken away. 1974 I think was the last time that the Loyalist people held their head up, the last time they had got a lift from the depravity that they felt themselves in, and how everything was now lost.

The age-old problem we’ve always had is that the ordinary working class were used again. They were brought out of the rabbit hole and when the dirty work was done and over, and all the plaudits had been handed out, they were shoved back into the rabbit hole again. That’s the difficulty of being associated with the Loyalist paramilitaries. You get all these ‘great’ people as they did in 1974, joshing up against you to get their photograph taken alongside you. But if you’d had dared mention the fact you were thinking of marrying one of their daughters, they would run a mile. So that’s the way we’ve been treated down through the years.

There was something, as I said earlier, about Hughie Smyth and myself – how we could see the divisions being played out within Stormont itself, between the various people who were making up the Executive. We knew for a fact and we heard afterwards that the Executive was about to split. The one thing we did have was of course, the success of the Strike – if you call it a success – was marvellous weather. If it had been raining, the wee-ins running out of the house, the women would have went crazy. They were outside; they were having picnics, they were having barbecues. The weather was absolutely superb. And of course, my great friend Paddy Devlin – he decided that he didn’t want to create any hardship for anybody and paid everybody the dole three weeks money in advance. To me, that was the commitment and the make of the man, and Paddy and I remained great friends after that. Indeed I was one of the people who sponsored his European Election campaign (in 1979), not that it did him any good. But that was the measure of Paddy Devlin. His thought was for the ordinary working class people and therefore he didn’t want to see them starve.

One thing that was never given the same space in the media as the Strike was was the three-day conference that I called of the Strike Committee a week or two after the Strike was over. We held it in Vanguard headquarters and it was the full Committee except the politicians – they were kept out of it. We told them we would give them a shout when we wanted them. The whole concept was how did we see Northern Ireland? What did we want for our people in Northern Ireland? It might surprise you to know that it was the overwhelming, unanimous decision that we had to find a new way of governing Northern Ireland, and we had to find a new way of governing Northern Ireland that involved the two peoples of Northern Ireland. We demanded that our politicians would go and find a settlement with Catholic representatives. We demanded that the paramilitaries would not be used again, and therefore don’t be coming crying to us if you don’t do it this time.

That was the feeling of the ordinary working class representatives through the paramilitaries; the men who had continually done the dirty work. The men who finished up in jail when their politicians finished up in Stormont on the fat wages. Of course it’s all very well doing the dirty work and doing the will of the politicians and allowing them to exploit and manipulate you, but when you start to bite back – that’s not what they want at all.

What was the Strike about? It was a mixture. I know that people have tried to put one caption on it from time to time. It was about this, ‘We didn’t want Catholics in government’. Yeah there were those who didn’t want Catholics in government. There were those who didn’t mind Catholics in government, but they didn’t want Republicans. There were those who wanted Stormont back with majority rule, as it was. There were those who wanted Stormont back, but they wanted a whole new Stormont.

To me – and I still hold this view – it has institutionalized the divisions in our community. We have not seen the evolution of proper politics. It has been a direct result of the decisions that have been taken by Westminster and it’s been a direct result of Westminster and the Irish Government – but particularly Westminster – doing deals behind people’s backs which we’ve seen, and I’ve talked about this the last forty years. You cannot build a society if you go to one side and give them guarantees because very quickly they’ve got to go to the other side and give them guarantees. So you’re trying to build things on guarantees.

I argued within Beyond the Religious Divide that we’d have a new Constitution, a new Bill of Rights, that applies equally to every citizen of the state, protected by a Supreme Court, whose Supreme Court Judge could be appointed by a friendly country such as the United States for a period of ten years, and that we would try and allow our people to elect our representatives on purely political terms, and not the donkey carrying the biggest Union Jack or the goat carrying the biggest tricolour. It’s an indictment on us – it’s an indictment on everybody that has brains in this country and a vision for this country, to try and build a society in which we don’t recognize that whatever we’re doing is going to affect our children for generations to come. Unless we find a way forward, of allowing the evolution of proper politics to take place in this country – in which the talents of our two communities can be pulled together to govern this country – then we’re damned for the rest of our lives. We’re always going to be governed by the border.

Every time we have a problem, and we said this in the seventies, and I said it after the Good Friday Agreement when they all came out looking for the Loyalists to see what they had agreed to – they didn’t put any soul into that Agreement; there was no heart in it. And every time one group was getting into bother we should have trying to help them get out of their troubles – not be digging their hole bigger for them. Unless we can see that vision: that regardless of man’s religious beliefs, that if he’s the best person in the country to do a particular job then that man or that woman should get that job, and it’s the same in government. What we have at this minute in time is a system of government that only perpetuates the Troubles.

I’ll leave you with a question I ask when we do our big programmes to Belgium with young people in particular from both communities (and from the adults but more particularly with the kids). If children are not born bigots, where do they come from? Who makes a bigot? How does a person become a bigot? And I’ll bet you a pound to a penny there’s not one of you in this room today who could hold up your hand and say ‘I have contributed to that bigotry’. Each and every one of us in our own capacity have contributed to that bigotry. The 74 Strike was a time when Loyalist people after such a battering lifted their head for a short period of time. And the only way in which we’re going to get an Agreement in this community is to remove the fears of the two communities by our actions, not by just words, but by actions.

Fourteen years ago when I was in Canada I was visiting the First Nation people, and I got very friendly with one of the Chief’s sons. We were out having a beer one night and he was telling me about all the troubles that they have in the reservations with religion – I knew there were drink and drugs, but I didn’t realize there were religious problems in reservations. I said to him ‘What are your thoughts for the future?’ He said ‘Glen, what we do within our people is – we have to think in the seventh generation’. I said ‘What do you mean the seventh generation?’ He said ‘We don’t think about making laws that’ll affect our people, and our children and our grandchildren – we think in terms of how it’ll affect the seventh generation of our people’. Now that’s vision, and sadly I’m afraid to say that we’re lacking that vision here in this province. I think that the only way – if we want to survive, if we want to come through this – is we have to draw on the combined talents of our two communities to get us through it. We can’t do it on our own, the Loyalists. The nationalists can’t do it on their own. Unless we accept the fact that this is a basic consideration for all of us then we’re going to go on the same way. Don’t listen to what people are telling you about ‘That’s solved, this is solved’ – it won’t be solved because in ten years’ time it’ll start all up again.

We’ve got to get back to the beginning. We’ve got to start from scratch and we’ve got to pull in people with vision who can convince our others that this is the only way forward. And all I want to say to you is just thank you very much for the opportunity, and I’m going to get back into retirement again after this. Thank you very much.”

*Credit to co-organiser Dr Connal Parr for originally transcribing Glen Barr’s speech.