The Murder of Frankie McStravick: 1972

The bullet that finally killed Frankie McStravick travelled through time and caused untold trauma

January 2025

If ever a week could be described as good and bad then last week was it. On Wednesday 15 January I received an email from PRONI notifying me that several files I had requested in 2021 were ready to collect. Many of these documents related to activities of the so-called “heavy squad” of the Sandy Row UDA in the early 1970s and a range of horrific murders individuals associated with them carried out in the summer of 1972.

I will write more about the files and how they fit in with some of the ongoing research I am carrying out (the expanded follow-up to Tartan Gangs) but the purpose of this post is to remind people of the vast ripples that sectarian, or any type of murder, can cause.

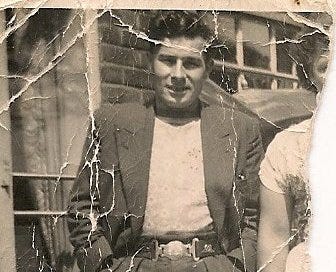

One of the coroner’s inquest reports related to Frankie McStravick, a Catholic man who was found murdered on 27 July 1972 in South Belfast.

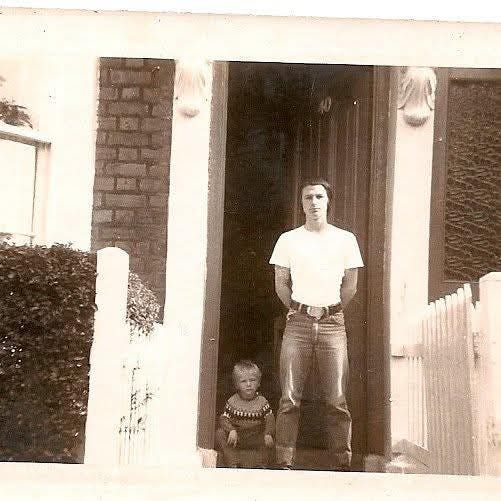

In recent years I had the privilege of striking up an online correspondence with Frankie’s nephew, Seán McGrady. Seán, whose mother was Frankie’s sister, was born in 1955 and he had written two novels - The Backslider and The Bastard Pleasure; he could often be found posting on Twitter. During his formative years he lived in Wolseley Street, behind Queen’s University Belfast and spoke often about his childhood in the 1960s before the Troubles. Like many unfortunate people in Northern Ireland at the time, sectarian conflagration would eventually swing its remorseless pendulum across the lives of the McGradys and leave the detritus of trauma and grief scattered through families and subsequent generations.

When I got notification from PRONI that Frankie’s inquest file was ready, along with the court files of the men who murdered him, I immediately messaged Seán. We hadn’t corresponded for several months, but there was nothing unusual about that. Seán would keep me right on facts and he put me in touch with a former RUC officer who was part of a team which secured a conviction for Frankie’s murder in the mid-1980s. Seán was keen to see these files for himself.

A few hours later, I got a message back. It was from Seán’s daughter. He had passed away in 2024.

Seán and the former RUC officer he put me in touch with* were both deeply traumatised by the murder of Frankie and the events of over 50 years ago.

19 November 1971

Frankie and his teenage daughter Shirley left their home in Darlington and travelled across the water to a dramatically changed city from the one he had left in the 1950s. Frankie McStravick and his wife had been having issues with their marriage and despite leaving four siblings behind in Darlington 14-year-old Shirley preferred to be with her dad. Frankie was a former IRA member who had non-sectarian tendencies which would have been close to the ethos espoused by Cathal Goulding and the Officials. He had served in the British Army during the Second World War before obtaining a medical discharge in 1951.

On their arrival in Belfast Frankie and Shirley stayed with Seán’s mother and the family in Wolseley Street. Frankie was originally from the Falls Road area. He wanted to be close to his sister and the McGrady family but didn’t want to impinge on them. Just before Christmas 1971 Frankie found a house to rent in Maryville Street. It was only a ten minute walk to the McGrady household. Unfortunately for Frankie the tumultuous polarisation which had gripped the city was being sharply felt as the winter of 1971 turned to the spring of 1972. Although close to Ormeau Avenue, Dublin Road and the Markets area Maryville Street was largely an arterial route that fed into Donegall Pass.

While there had always been a significant number of Catholics living in Donegall Pass it was a staunchly loyalist area. ‘David Smyth’, then a young teenager who would join the YCV as a schoolboy, recalls that the killings of the Scottish soldiers in March 1971 had a detrimental effect on the already deteriorating relationship with the remaining Catholics who lived in the area: ‘You could…feel the temperature rising. Prejudices would start coming out, fears would start coming out…have we got a Trojan horse here? You’ll always find a small element who want to push, agitate and propagate myths or deception and say we need to actually get rid of these people.’ As a 14-year-old however Smyth personally concedes that he wasn’t exactly sure what to make of the increasingly volatile atmosphere: ‘I gotta be quite honest and say I don’t think I had a great understanding…I was still very much into boy things, and I suppose going to school and at that time I was going to church. I knew something was wrong. You start watching and observing.’

During his first few months back in Belfast Frankie cut something of a tragic figure. He was unemployed and lived off his army pension and unemployment benefit. When he was depressed or upset he would drink and he wasn’t particular about the pubs he frequented. Frankie’s estranged wife Lilian had become fed up with his heavy drinking, although it was clear that she loved him, describing him as a likeable person who was quiet and reserved when not drinking. After a few drinks he was prone to being ‘nasty’ and talking too much about his political allegiances. Frankie was still in love with his wife and wrote to her every week from Belfast in the hope that the couple could eventually reconcile.

As more and more men joined the loyalist vigilantes and paramilitaries in early 1972 the public houses on Donegall Pass and other areas became natural meeting places for those involved in defence and militant activities. In this context Frankie’s drinking habits became even more perilous.

25 July 1972

On Tuesday 25 July Shirley McStravick left her father at home at around 6.45 p.m. When she returned a couple of hours later at around 8.50 p.m. she found a note on the table which had been written by Frankie. It instructed her to take several beer bottles and a lemonade bottle to the shop to get money on them. Shortly after doing this Shirley walked to the Capital Bar on the Dublin Road and asked the barman could she see her father. Frankie came to the door and greeted his daughter before giving her 10 ½ pence for lemonade and promised her that he would be ‘round home shortly’. When she awoke the following morning Shirley discovered that her father’s bed had not been slept in. Fearful for his safety she reported him missing to the police at Donegall Pass RUC station at 11.00 a.m. on 26 July.

At some stage the previous night Frankie had left the Capital Bar and instead of going home he walked the short distance to the Oak Bar on Donegall Pass. As he took a seat at the bar and ordered a drink Frankie engaged the barman in conversation. Noticing that they both had black eyes Frankie asked whether the barman had been involved in the trouble down at Castle Street earlier in the day. He explained that is where he had received his black eye.

As the conversation went on the barman looked over to a table where members of the UDA were sitting drinking. He noticed the men giving each other funny looks as with each drink Frankie began to talk more openly about his political convictions. After a short period of time Frankie was asked to accompany the UDA men into the back lounge of the bar. The barman, himself a member of the UDA in Sandy Row, later recalled that ‘… when they were holding him in the lounge there was a lot of fighting and a brave ruckus going on.’ One of the Donegall Pass UDA men emerged from the lounge and asked for the number of the Lily Bar on Sandy Row.

A phone call was made and soon after Robert James Watson who had been involved in killing a mentally vulnerable man called Charles Brendan Connor only four weeks previously arrived at the Oak Bar. A heated discussion took place between the UDA men from the Pass and Sandy Row, the latter of whom believed that the fate of McStravick was the ‘problem’ of the Pass men. Eventually a van and gun were called for and Frankie was taken out the side door of the bar and brought to Sandy Row where he was shot dead, carried a short distance in a wheelbarrow and dumped on railway sidings near the Great Northern station.

Frankie’s badly beaten and lifeless body was only discovered over a day later by two young boys from the Sandy Row area who had been playing near the railway tracks. Plain clothed RUC officers made their way to Wolseley Street to inform Frankie’s sister of the grim discovery. Seán McGrady, then a teenager, remembers there being ‘pandemonium’ in the parlour as his mother was told of her brother’s murder. ‘My father had to identify Frankie’s body which was a horrendous experience for him as Frankie was left in a very bad way. My mother couldn’t bring herself to do it.’

According to Seán’s family he lived with the trauma of these events up until his death. It was evident in our correspondence that he had been irreversibly marked by the cruel actions of those who murdered his uncle.

Frankie was one of a number of vulnerable men who were killed that summer by the UDA in Sandy Row.

In loving memory of Seán McGrady.

*If you're the RUC officer, can you please email me at gareth.mulvenna@gmail.com - I'd be keen to link in again